|

Is natural/organic wine healthy? That question has apparently been answered with a self-approving "yes" by some producers, marketers, and salespeople during this swelling natural wine wave. Natura, a large Chilean producer of organic wines found in many American supermarkets, identifies themselves confidently as "High quality, clean and healthier wines" on their website. Another major producer of organic and biodynamic wines, Frey Vineyards of Mendocino, presents a more nuanced justification for their grape growing and winemaking choices. It's not blazed across their homepage. However, they still claim "For nearly thirty years we have been making delicious organic wines that are natural, healthful and enjoyed by wine lovers across the globe." While producers of organic or natural wines make only occasional health benefit claims, retailers don't shy away from making it their primary sales pitch. Several natural wine subscription clubs have emerged that market their offerings as healthy products. The Wine Fellas, based out of Napa, feature "wines that are friendly to all diets and healthy lifestyles." Dry Farm Wines (another subscription club) slaps you across the face with their health claim. Their home page boldly states they are "The Only Health-Focused Organic Wine Club in the World." Not only do they meticulously select organic wines to sell, they also perform a chemical analysis to substantiate the "highest standard of health." Dry Farm Wines even reaches so far as to guarantee no headaches or hangovers. A smattering of endorsements appears on their website from people I deem to be health nuts heralding the wine's compatibility with their diets. I recently ran into an old friend who jumped at the opportunity to tell me about Dry Farm Wines and how healthy their products are. This friend exhorted me on the wondrous powers of the wines' harmony with her lifestyle, how they reportedly allow you to stay in a state of ketosis metabolism, are a wholesome food, and don't result in grogginess due to the absence of histamines and sulfites. She continued to lecture me on how wine is made in a distillery, sugar is added to all other wines, dry farming translates to healthier wine, so on and so forth. I didn't have time to debate that 1) drinking on a serious weight loss diet is probably a bad idea, 2) wine is made in a winery, 3) many, many wines from small producers contain zero residual sugar nor contain added grape concentrate, 4) dry farming's main (and perhaps sole) benefit is water conservation, and 5) scientific study has proven sulfites don't cause hangovers and histamines probably don't, either. As I researched Dry Farm Wines, it's easy to see why so many people fall for Fake News. Modern science isn't perfect, but nobody promoting this stuff cites any peer-reviewed science. Despite all the online claims, wine is simply not a health food. Small daily intake of compounds like resveratrol and even alcohol have been shown to benefit your heart health and blood pressure. However, the benefits have been hyperbolized in the name of grabbing attention. The harm of excessive alcohol consumption poses a bigger health threat than the potential benefits. It's important to distinguish between marketing and facts, which Wine Fellas rightfully does in some blog posts buried deep in their website (even with links to studies). The truth is, you can buy resveratrol supplements at your local drug store or get higher doses naturally by eating certain fruits. In April 2017, CNN published an informative and well-researched article debunking exaggerated wine health claims. They focus on the benefits versus risks to heart health and cancer from alcohol consumption. Their conclusion: "drinking wine isn't more important than eating a nutritious diet, engaging in regular exercise, and avoiding smoking." Healthy Vineyards = Healthy People The real, measurable health impact from organic or biodynamic practices is directly on the people working the vineyards and the surrounding residents. Scientific studies have shown for decades that inhalation of synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides have a serious effect on the respiratory health of vineyard workers. California has very serious pesticide regulations, and some parts of Sonoma require vineyard managers to notify neighbors before spraying to avoid exposure. Vine Pair has an informative article exploring the practices of organic farming, permitted pesticides, and the effect of pesticides on health. It's worth a full read, but in summary, it's very doubtful drinking organic wine has any health benefit to the consumer over conventional wine. The author's concluding recommendation is to not worry about the organic label, but to drink wine from small producers, who likely take better care of their land and their grapes, versus large-scale industrial wine (even if it's certified organic). This has a bigger positive effect on the vineyard workers and surrounding community than on any perceived health of the drinker. Everything in Moderation The sheer number of people promoting natural wines online is insane. I'm all for putting more wholesome foods in our bodies. I try to err on the side of common sense even if there isn't hard science backing up every single "healthy" choice. I would rather not drink wine grown with synthetic pesticides, containing loads of sulfites and commercial additives. Sometimes the science is there, sometimes it hasn't caught up yet. However, the fanaticism and fundamentalism about natural wines is edging into Crazy Town territory. After investigating many bogus marketing claims and factual scientific studies, the safest conclusion must be "everything in moderation" and "use common sense". If you want your wine purchases to have a positive health impact, make the effort to help the people who grow wine grapes and the surrounding farm communities. If you want to protect your own health, eat balanced foods, limit your sugar intake, exercise regularly, and drink lower alcohol wines in moderation. That's what any doctor would tell you. 1. I expect to get some fervent feedback about this article. I welcome any evidence on the healthiness of natural wines, histamine headaches, pesticide content in wine itself, etc. that is rooted in science and not simply anecdotal accounts. I'm never afraid to admit I'm wrong when exposed to new facts. 2. The Dry Farm Wines founder does appear to base some of his claims on established facts and has some industry insights with which I agree. I'm not accusing him of being a snake oil salesman, but I think it's an extreme interpretation of winemaking standards. His customers and online health fanatic bloggers buy the pitch hook, line, and sinker without understanding what they're talking about. Wine is a very nuanced issue, which I intended to partly clarify in this article.

0 Comments

An article from Eater.com which I read last month turned my attention to wine labels. The entire span of my drinking life has seen a proliferation of eye-catching labels and bottles. Many studies, such as the one cited in this article, reinforce the strength of dynamic labeling. "And a 2015 Gallo Wine Trends Survey found that millennials are four times more likely than Baby Boomers to buy a wine based on the label. They are looking for labels with originality and personality, while Baby Boomers pick labels based on region of origin and taste. Nielsen found a similar trend. Millennials want labels that are "bold and distinctive," while baby boomers want more traditional designs."

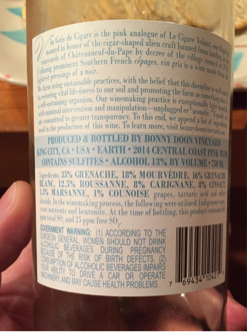

What, really, does a label (or the whole bottle's presentation) tell us? Certified wine professionals would point to European labeling rules as the ideal model. Understanding the label cues can lead to effective conclusions on wine quality before you ever drink it, as we're taught in WSET classes. However, a serious amount of studying and geography skills are required to effectively remember the vast difference between a Pouilly-Fuissé (Chardonnay from the Macôn region of Burgundy in eastern France) and a Pouilly-Fumé (Sauvignon Blanc from Loire in western France), or the difference between Vino Nobile di Montepulciano (red wine made from mostly Sangiovese near the town of Montepulciano in Tuscany, which is on the west coast) and Montepulciano d'Abruzzo (a red wine hailing from the Abruzzo region on the east coast made from the Montepulciano grape). For this reason, many importers have altered back-of-the-bottle labels on European wine to include the grape varieties for their "less sophisticated" American consumers. The American domestic wine industry came of age in the late 20th century with varietally-labeled wines, and it's shaped American consumers. I personally don't think that's a bad thing. However, in defense of the Europeans, once you learn the classification systems, it's a lot easier to understand that you'll likely get a better quality of wine when you buy a Chateauneuf-du-Pape AOC than a bottle of Côtes du Rhône AOC. The U.S appellation system is sometimes equally confusing. You must study the appellation maps and read wine reviews to understand that a Russian River Valley AVA Pinot Noir is generally of higher quality than one from the North Coast AVA (which can include fruit grown almost anywhere in six Nor Cal counties). For better or worse, the AVA (American Viticulture Area) designations don't have the same quality-based regulations that the European AOCs or DOCs do. For Americans without a deep knowledge of wine, the only way to tell that a Rochioli or DuMOL Pinot Noir is far superior to a La Crema Pinot Noir is the price tag. European consumers have the upper hand with quality guarantees, but U.S. wineries wouldn't fare well with a similar amount of encumbering regulations and classifications. Still, consumers lose in either labeling system. In my opinion, one of the biggest hurdles to the success and expansion of premium New World wines is the opaque nature of their identity or blatant misdirection/concealment of origin with marketing schemes. In 2015, the top three selling wine brands in the U.S. were Barefoot, Sutter Home, and Franzia. Peruse the bottom two shelves of supermarkets and you'll find the other brands like Apothic and Cupcake that land in the top 20. These are all wines without "provenance", or in wine-speak, an identifiable source. They're made from grapes sourced from the cheapest contract vineyards all over California. To keep consistency of taste year after year, these wines are seriously doctored with additives, chemicals, and interventionist techniques like reverse osmosis to reduce alcohol content. In order to compete with the mega-brands like Constellation, Gallo, The Wine Group, and Treasury Wine Estates who own all the aforementioned brands, smaller sub-premium brands focus lots of energy on branding and label design. The main example in the Eater article, Mouton Noir wines, is a serious winemaker producing better-than-plonk wines. Yet his labels focus on catching attention, looking hip, and making puns. I suppose this is the strategy you have to take to stand out and capture customers. I suppose it speaks well to your target audience of Millennials. Conventional advertising theory would assert that this is the winning strategy. Make your brand unique. Stand out. Catch the customer's eye. Sadly, this is an effective strategy for sales but not for informing the customer of anything substantial. The label strategy is just like any other consumable product: buy this lifestyle, buy this emotion, buy this to show off to your friends. These labels don't educate the consumer or guarantee a product's quality. I recently took the above photo of the back label on a bottle of a Vin Gris de Cigare from Bonny Doon. Owner Randall Graham is known for being a trendsetter among the American wine industry, and I hope others follow suit. I love the amount of useful information they put on a label. You can see they list the grape varietals, the winemaking style, the fact that they added tartaric acid and yeast nutrients, used bentonite for fining, and exactly how much sulfur dioxide exists in the bottle. This is a phenomenal amount of info for consumers. If you're a natural wine zealot, you may think 60 ppm of SO2 is too much, or be disappointed that they had to acidulate the wine. But at least those zealots know what is in the bottle and can decide to compromise their principles, or refuse to drink it. I don't universally avoid those winemaking techniques, especially on a wine in this price range (<$20). However, when I'm buying a $30+ bottle of wine, I expect to pay for better quality grapes, which come from greater attention in the vineyard and cellar. I'm really disappointed when I discover a high-end or boutique producer is charging top dollar but acidulating, watering back, or adding powdered tannins to their wines. I want to be paying for grapes of the highest quality, where my dollar directly goes to the attention paid to the vineyard. I don't want to be paying for inferior grapes that are "corrected" into decent wine. All I'm buying at that point is marketing. Put whatever design or artwork you want on the front label. I understand that winemakers or corporations have to grab attention on the shelf or that they want to express their artistic style. Back labels like those on Bonny Doon wines provide a commendable level of transparency. Other wine producers should take notice and follow their lead. For the past few months, professional wine journalists and bloggers have been debating the concepts of the "hipster somm" and "natural" winemaking. The debate boils down to this:

1) Apparently younger somms in NYC have started to favor wines made in what they believe to be Old World style: low in alcohol, high in acid, and made by winemakers who swear to zero intervention; 2) These somms even like wines with hints of Brettanomyces, a verifiable wine flaw caused by undesirable yeast strains that make wine smell like wet barn animals (sulfur); 3) The somms favor adherents of "natural" winemaking, which is typically defined by biodynamic farming, not adding excessive (or any) sulfites as preservatives, using only native vineyard yeasts, and not doctoring wine with tartaric acid, sugar, grape concentrate, etc. to make up for a flawed wine. 4) Wine journalists hit back that the form of "natural" winemaking which "hipster somms" favor equates toward asceticism. The strictest form of non-intervention imposed by the hipsters leads to bad wine. Modern methods and New World styles are not inherently wrong. OK. Clear as mud? What I can gather from this ongoing war of words is a lot of over-exaggeration. The desire for authenticity and integrity in wine is nothing new or hip. People who pay a lot of money for fine wines want a pure expression of the grape varietal(s). But so many wines today are clouded in mystery as to their contents. Along with the organic and non-GMO movements, the natural wine movement is rightly seeking clarity about what's in the bottle. However, some purists take it pretty far. Is it defiling or desecrating the wine to add small amounts of tartaric acid to balance out flabbiness? Is using a controlled, cultured yeast instead of native vineyard yeast an abomination? No. The problem is that, unless a vintner details their winemaking process on their website or on the bottle's label, you have no clue how that wine is made. A $5 wine you find on a liquor store shelf is most certainly doctored with sugar, acid, and other additives to make up for cheap quality. But the $15, $20, or even $50 bottle you buy for a special dinner may be just as doctored up, too. The hipster somms may be fanatics, but they're driving the industry to improve their transparency, and through that - each producer's winemaking skills. Wine journalist Monty Waldin does a stellar job in clarifying the debate from a knowledgeable insider's perspective: https://grapecollective.com/articles/monty-waldin-on-hipster-somms-and-why-black-magic-wine-is-delicious-wine |

Blog

Other non-travel ramblings on wine and business. Archives

December 2018

Categories

All

|

|

All content is original property of Vineration unless otherwise noted.

Not permitted for reproduction. © COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed