|

Is natural/organic wine healthy? That question has apparently been answered with a self-approving "yes" by some producers, marketers, and salespeople during this swelling natural wine wave. Natura, a large Chilean producer of organic wines found in many American supermarkets, identifies themselves confidently as "High quality, clean and healthier wines" on their website. Another major producer of organic and biodynamic wines, Frey Vineyards of Mendocino, presents a more nuanced justification for their grape growing and winemaking choices. It's not blazed across their homepage. However, they still claim "For nearly thirty years we have been making delicious organic wines that are natural, healthful and enjoyed by wine lovers across the globe." While producers of organic or natural wines make only occasional health benefit claims, retailers don't shy away from making it their primary sales pitch. Several natural wine subscription clubs have emerged that market their offerings as healthy products. The Wine Fellas, based out of Napa, feature "wines that are friendly to all diets and healthy lifestyles." Dry Farm Wines (another subscription club) slaps you across the face with their health claim. Their home page boldly states they are "The Only Health-Focused Organic Wine Club in the World." Not only do they meticulously select organic wines to sell, they also perform a chemical analysis to substantiate the "highest standard of health." Dry Farm Wines even reaches so far as to guarantee no headaches or hangovers. A smattering of endorsements appears on their website from people I deem to be health nuts heralding the wine's compatibility with their diets. I recently ran into an old friend who jumped at the opportunity to tell me about Dry Farm Wines and how healthy their products are. This friend exhorted me on the wondrous powers of the wines' harmony with her lifestyle, how they reportedly allow you to stay in a state of ketosis metabolism, are a wholesome food, and don't result in grogginess due to the absence of histamines and sulfites. She continued to lecture me on how wine is made in a distillery, sugar is added to all other wines, dry farming translates to healthier wine, so on and so forth. I didn't have time to debate that 1) drinking on a serious weight loss diet is probably a bad idea, 2) wine is made in a winery, 3) many, many wines from small producers contain zero residual sugar nor contain added grape concentrate, 4) dry farming's main (and perhaps sole) benefit is water conservation, and 5) scientific study has proven sulfites don't cause hangovers and histamines probably don't, either. As I researched Dry Farm Wines, it's easy to see why so many people fall for Fake News. Modern science isn't perfect, but nobody promoting this stuff cites any peer-reviewed science. Despite all the online claims, wine is simply not a health food. Small daily intake of compounds like resveratrol and even alcohol have been shown to benefit your heart health and blood pressure. However, the benefits have been hyperbolized in the name of grabbing attention. The harm of excessive alcohol consumption poses a bigger health threat than the potential benefits. It's important to distinguish between marketing and facts, which Wine Fellas rightfully does in some blog posts buried deep in their website (even with links to studies). The truth is, you can buy resveratrol supplements at your local drug store or get higher doses naturally by eating certain fruits. In April 2017, CNN published an informative and well-researched article debunking exaggerated wine health claims. They focus on the benefits versus risks to heart health and cancer from alcohol consumption. Their conclusion: "drinking wine isn't more important than eating a nutritious diet, engaging in regular exercise, and avoiding smoking." Healthy Vineyards = Healthy People The real, measurable health impact from organic or biodynamic practices is directly on the people working the vineyards and the surrounding residents. Scientific studies have shown for decades that inhalation of synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides have a serious effect on the respiratory health of vineyard workers. California has very serious pesticide regulations, and some parts of Sonoma require vineyard managers to notify neighbors before spraying to avoid exposure. Vine Pair has an informative article exploring the practices of organic farming, permitted pesticides, and the effect of pesticides on health. It's worth a full read, but in summary, it's very doubtful drinking organic wine has any health benefit to the consumer over conventional wine. The author's concluding recommendation is to not worry about the organic label, but to drink wine from small producers, who likely take better care of their land and their grapes, versus large-scale industrial wine (even if it's certified organic). This has a bigger positive effect on the vineyard workers and surrounding community than on any perceived health of the drinker. Everything in Moderation The sheer number of people promoting natural wines online is insane. I'm all for putting more wholesome foods in our bodies. I try to err on the side of common sense even if there isn't hard science backing up every single "healthy" choice. I would rather not drink wine grown with synthetic pesticides, containing loads of sulfites and commercial additives. Sometimes the science is there, sometimes it hasn't caught up yet. However, the fanaticism and fundamentalism about natural wines is edging into Crazy Town territory. After investigating many bogus marketing claims and factual scientific studies, the safest conclusion must be "everything in moderation" and "use common sense". If you want your wine purchases to have a positive health impact, make the effort to help the people who grow wine grapes and the surrounding farm communities. If you want to protect your own health, eat balanced foods, limit your sugar intake, exercise regularly, and drink lower alcohol wines in moderation. That's what any doctor would tell you. 1. I expect to get some fervent feedback about this article. I welcome any evidence on the healthiness of natural wines, histamine headaches, pesticide content in wine itself, etc. that is rooted in science and not simply anecdotal accounts. I'm never afraid to admit I'm wrong when exposed to new facts. 2. The Dry Farm Wines founder does appear to base some of his claims on established facts and has some industry insights with which I agree. I'm not accusing him of being a snake oil salesman, but I think it's an extreme interpretation of winemaking standards. His customers and online health fanatic bloggers buy the pitch hook, line, and sinker without understanding what they're talking about. Wine is a very nuanced issue, which I intended to partly clarify in this article.

0 Comments

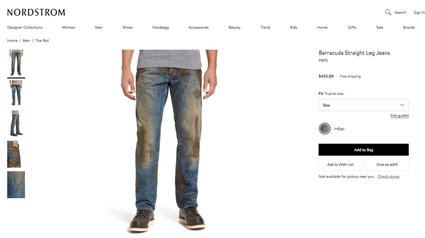

Recently a strange fashion trend went viral on the internet: dirty jeans. Denim company PRPS (read: purpose) was skewered on the web for selling $425 men's jeans with fake mud at Nordstrom. Why would you pay $425 for fake dirty jeans when a pair of $25 Wranglers and a day spent working on a farm reaches the same result? Average people took Nordstrom and PRPS to the woodshed for the absurdity of the existence of these jeans. An NPR columnist rightly tore into PRPS and the uproar in this piece. I love that the author drew out the contradiction over PRPS creator Donwan Harrell's definition of authenticity. "The brand uses denim woven on vintage looms. Harrell started it in response to what he saw as a lack of "authentic" jeans on the market. Even the name — PRPS, as in Purpose — is a callback to a time when jeans were designed as workwear, with a real function. In an interview last year, Harrell invoked authenticity — or the emulation thereof — as a core design principle." I'm bringing up this fashion-related issue because the same principle applies to the distortion of "authenticity" in winemaking. The emulation of authenticity is a key principle for industrial wine. Corporate strategy is to convince consumers to buy wine based upon branding and perception, even if it is not rooted in truth. Unjustifiable claims such as "sourced from the best vineyards in California" are made all the time. Also, brands which have no association with an actual location or person are sold on the strength of the false brand association. I don't find too much evidence of corporations starting a "_____ Family Wines" brand, but frequently they buy a family or personal brand and retain the name. It's the most valuable asset of that company, more so than the vineyards or the production facility. My favorite example is of Kim Crawford Wines, the omnipresent New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc producer. The actual man Kim Crawford sold his company to Constellation Brands in 2003, and was henceforth prohibited from using his own name in any commercial venture. The current website refers to Kim's story many times without acknowledging he is no longer associated with the winery. And Kim is unable to even use his name with his new winemaking venture, Loveblock Wines. Not only are personal names used deceptively, but so are place names. The Don Sebastiani and Sons wine company produces a Cabernet Sauvignon called Gunsight Rock. The grapes come from Paso Robles, but the actual Gunsight Rock is 250 miles north in Sonoma County. It's a locally-famous overlook in Hood Mountain Regional Park with my favorite stunning views of Sonoma Valley. Sebastiani pitches the wine thus: "Gunsight Rock wines highlight the richness and beauty of California’s wine country. Wild, intense and adventurous, they evoke the feeling of the sun on your face, the wind at your back, and the view of one of the world’s most picturesque wine regions spread out before you." Most people probably don't know and don't care where Gunsight Rock actually is. The tagline insinuates that the "picturesque wine region" would be Paso Robles, which the label designates as the origin. But the location of the landmark and the vineyards are totally unassociated. This inaccuracy is a violation of authenticity and a deliberate decision to manipulate truth to suit a brand. (Coincidentally, the Sebastiani family no long owns Sebastiani Vineyards, which was sold to the Foley Wine Group in 2008). The Kim Crawford and Gunsight Rock examples are far more nuanced than PRPS's ridiculous filthy jeans. At $425-a-pop, it's quite easy for shoppers to guess that the jeans weren't actually dirtied up on a farm, nor are the idiotic purchasers of these jeans trying to pass themselves off as farmers or construction laborers. It's far more difficult for people to discover that Kim Crawford has nothing to do with wine sold under his name or that Gunsight Rock is nowhere near the vineyards which grow the grapes.

However, the common thread is that falsehood in branding is rampant. Consumers are explicitly or implicitly convinced that a product is authentic: that it's origin and production honestly match with the brand marketed at them. Anything less than that is disrespectful and deceitful. I'm guessing that PRPS learned a lesson from their exposure. What will it take for big wine corporations to learn their lesson? The launch of Alit Wines's first release has been making the rounds on the blogosphere the past couple months. This new Oregon winery is taking a stab at transparency, a subject with which I'm obsessed.

This brand was created by Mark Tarlov, a modern Renaissance man whose accomplishments include founding celebrated Oregon wineries Evening Land Vineyards and Chapter 24 Vineyards, being a Hollywood producer/director, serving as a special antitrust attorney in the U.S Department of Justice, and working as a speechwriter for Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger. Impressive. With this latest venture, Tarlov & Team are taking a stab at making a wine that is more transparently grown, vinified, and sold. Their effort is really worth taking note of and watching. By transparency, Alit means they are going to tell consumers exactly how the wine grapes are grown, by what process they are turned into wine, and what it costs at each step. They are not the first wine producer to do these things, but to my knowledge, they're the first to do them ALL. From Alit's infographic above, you can see a basic presentation of their farming and winemaking methods, cost breakdown, and sales strategy. I read a few favorable articles about their wines from Bustle and Quartz, and I poked around the Alit website. I have a few critiques about how they present the vineyard origins of the wines, the lack of enological details like pH and TA for the wine geeks, and the fact that you can't even figure out the Pinot is a 2015 vintage. I'm also perplexed as to why they're selling grower Champagne. But we shouldn't dwell too long on the minor details. Let's focus on the purpose. In Alit's own words, this is why they are doing business this way: "Alit is a new kind of wine brand that’s stripping away all of the extra layers between the winemakers (us) and the wine drinker (you). Our goal is to bring you closer to the story of our wine, the people who make it and the place that it comes from. We believe great wine should be made naturally and with integrity, with no synthetic ingredients or chemicals. We also believe the winemaking process should be shared with everyone, not just “wine people.” So we’re being fully transparent about what it costs us to make wine without compromise." As for their sales model, Alit will be solely direct-to-consumer (DtC), which has proven to be the fastest growing and most profitable way to sell wine in the online age. Of course, none of this means Alit's wines are going to taste good or be the best value for the money. But it does mean that wine drinkers will have a complete picture to make an informed choice about what they're buying. I give Alit a BIG round of applause for trying to transform the values of transparency and integrity into a business plan. I hope other wine brands are taking cues! |

Blog

Other non-travel ramblings on wine and business. Archives

December 2018

Categories

All

|

|

All content is original property of Vineration unless otherwise noted.

Not permitted for reproduction. © COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed