|

I'm excited to announce that some of my wine travel stories have been published by the Tampa Bay Fine Wine Guide!

I wrote a series of articles for them based on my travels in New Zealand. I've been to 41 wineries in NZ and chose 10 of my favorites, of which 7 made the final cut. Check out the online version using this link, and let me know what you think: https://issuu.com/thefinewineguide/docs/tbfwg_tp_2017_2/88 I'll also be reposting the stories in their entirety here on my Travel section for your reading enjoyment.

0 Comments

The launch of The Martha Stewart Wine Company was announced this week, and I read about it in a favorable Fortune.com article as reposted on Terroirist. The Martha Stewart Living portfolio is owned by the publicly traded Sequential Brands, a retail licensing company which paid $353 million to acquire Stewart's brands in 2015. I'm telling you all this because it represents so much of what I detest about wine marketing and sales.

The venture is nothing more than a deceptive operation to make loads of money peddling private label bulk wine. Per the company website, "The Martha Stewart Wine Co. is a direct-to-consumer wine service, bringing you wines that Martha Stewart loves. The Martha Stewart Wine Co. delivers carefully curated selections of these wines straight to your door." Five minutes of online digging is all it takes for someone with a little wine knowledge to see through that charade. Unfortunately, many consumers aren't that savvy. Martha Stewart's domestic wines are produced by "Saddlehorn Cellars" which is really ASV Wines, a huge private label and bulk wine operation with locations in San Martin (south of San Jose near Gilroy) and Delano (just north of Bakersfield in the cheap-wine-haven Central Valley). Online wine retailers frequently sell private label plonk, such as ASV's wines, and trick customers into "deals". I found a telling tale about a novice wine drinker lured by marketing tactics into a Groupon wine sale. The wine happened to be made by ASV, and nearly identical to the domestic selection "carefully curated" by Martha Stewart. This guy eventually connected the dots about the wine's origin and has an informative blog post about it. Many other wine subscription clubs, such as Winc, The Tasting Room, and Bright Cellars, similarly sell private label wine while using creative marketing to make it appear cool and authentic. Why does private label wine bother me so much? Thanks for asking.

According to the Fortune piece, "The wine delivery company intends to work with Chris Hoel, the former sommelier of famed chef Thomas Keller's The French Laundry, to consult vintners to develop the collection." For the sake of the suckers who subscribe to Martha's wine club, I sure hope they bring on a qualified somm to ditch the private label garbage and give these folks some honest product. Wine Folly beat me to the punch a few months ago on a goal I'd long ago set. Madeleine did the yeoman's work of cataloging most of the major corporate wine brands. This is a hugely important step for transparency in the wine industry. I'll say up front that I have no problem if people are happy drinking industrially manufactured wine or wine from a boutique winery that happens to be corporately owned. The problem for today's consumers is that the information is so hidden or obfuscated. By use of brand names, label design, or shelf talkers, wine corporations frequently deceive consumers into buying wine by making them think it is a hand crafted product or a family-owned venture. I would hope many low-to-mid priced wine consumers can infer that impersonal labels like Picket Fence (Bronco Wine Co.), Irony (Delicato), or Primal Roots (Constellation) are corporate products. No more than five years ago, I was buying similar $5-15 supermarket weekday wines to stay within a reasonable budget, without a care who the producer was. After my wine infatuation became serious, I started paying more attention to who makes my wine. And since moving to California, I been incurable. That's when I became aware of the flood of mergers and acquisitions in the wine industry. So many iconic brands or cult family producers have sold out to "Big Wine" over the past 10-20 years. That is their personal prerogative, and I won't speculate on their motives or retirement goals. The item I take issue with is that many brands bury the story and still pass themselves off as independent or family-owned wineries. There are more instances than I can count, especially in California. Here are few examples: MacRostie - Full disclosure: We are wine club members at MacRostie. We signed up in 2016 after visiting with my parents and enjoying what is arguably the best view in Sonoma County from their tasting room patio. Steve MacRostie sold the winery in 2011 to Lion Nathan USA, the American arm of an Australian beverage conglomerate. In all our visits, the staff has never mentioned the corporate ownership, nor is it stated on the website. We're told every wine club shipment is "personally hand-picked" by Steve MacRostie for our enjoyment. I doubt that; they're just trying to sell wine. He is still involved (at least in giving intermittent, pricey vineyard tours, and probably in final blending), but the omission of the facts is irksome. My parents directly receive most of the wine, of which the Chardonnays are decent, and the Pinot Noirs have noticeably improved over the last two vintages. MacRostie's vineyard sources are some of the best in Sonoma: Sangiacomo, Bacigalupi, Ricci, and more. We remain members so we can show off the view to vacationing friends, the wine is consistent, and the hospitality is polished. However, I'm constantly on the hunt for an independent Pinot producer with comparable views, in which case, I'll jump ship.

Talbott Vineyards - E&J Gallo purchased this family winery in 2015. The wine bottle back labels talk about how the wines are named after their kids, such as Kali Hart and Logan, which has continued even after the acquisition. The website touts founder Robert Talbott and his direct involvement. Talbott may be 100% still involved in management, but nowhere does their website or collatteral mention the Gallo acquisition. I picked up a bottle of the Kali Hart Pinot a couple years ago and enjoyed it for being well-balanced and drinkable. I've noticed a rapid national expansion of the brand. Now you can find it on every Safeway shelf. Imagery Estate - I recently had a friend tell me they are a wine club member here. They are a person that prides themselves on the unique and independent things in life, as many San Franciscans do. But Imagery is now owned by The Wine Group, peddlers of FlipFlop, Cupcake, Franzia boxed wines, and MD 20/20 blackout juice. The sale was completed in 2015 along with the sister Benziger Winery. Imagery certainly does have a beautiful property and the wine is highly praised. But I didn't have the heart at the time to tell my friend the real story. I fear the worst as time goes on for Benziger and Imagery wine quality under The Wine Group. Bottom Line - Corporate ownership, along with fruit sources and winemaking techniques, ought to be fully disclosed to consumers in an easy-to-understand method. Too often the winemaking is inflated by marketable terms to sound more impressive and corporate ownership is purposefully concealed. Only by investigating and revealing the truth are consumers able to make a fair, informed choice. An article from Eater.com which I read last month turned my attention to wine labels. The entire span of my drinking life has seen a proliferation of eye-catching labels and bottles. Many studies, such as the one cited in this article, reinforce the strength of dynamic labeling. "And a 2015 Gallo Wine Trends Survey found that millennials are four times more likely than Baby Boomers to buy a wine based on the label. They are looking for labels with originality and personality, while Baby Boomers pick labels based on region of origin and taste. Nielsen found a similar trend. Millennials want labels that are "bold and distinctive," while baby boomers want more traditional designs."

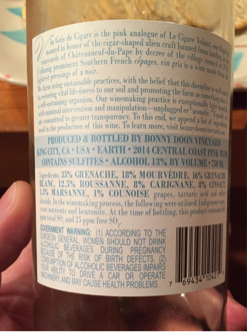

What, really, does a label (or the whole bottle's presentation) tell us? Certified wine professionals would point to European labeling rules as the ideal model. Understanding the label cues can lead to effective conclusions on wine quality before you ever drink it, as we're taught in WSET classes. However, a serious amount of studying and geography skills are required to effectively remember the vast difference between a Pouilly-Fuissé (Chardonnay from the Macôn region of Burgundy in eastern France) and a Pouilly-Fumé (Sauvignon Blanc from Loire in western France), or the difference between Vino Nobile di Montepulciano (red wine made from mostly Sangiovese near the town of Montepulciano in Tuscany, which is on the west coast) and Montepulciano d'Abruzzo (a red wine hailing from the Abruzzo region on the east coast made from the Montepulciano grape). For this reason, many importers have altered back-of-the-bottle labels on European wine to include the grape varieties for their "less sophisticated" American consumers. The American domestic wine industry came of age in the late 20th century with varietally-labeled wines, and it's shaped American consumers. I personally don't think that's a bad thing. However, in defense of the Europeans, once you learn the classification systems, it's a lot easier to understand that you'll likely get a better quality of wine when you buy a Chateauneuf-du-Pape AOC than a bottle of Côtes du Rhône AOC. The U.S appellation system is sometimes equally confusing. You must study the appellation maps and read wine reviews to understand that a Russian River Valley AVA Pinot Noir is generally of higher quality than one from the North Coast AVA (which can include fruit grown almost anywhere in six Nor Cal counties). For better or worse, the AVA (American Viticulture Area) designations don't have the same quality-based regulations that the European AOCs or DOCs do. For Americans without a deep knowledge of wine, the only way to tell that a Rochioli or DuMOL Pinot Noir is far superior to a La Crema Pinot Noir is the price tag. European consumers have the upper hand with quality guarantees, but U.S. wineries wouldn't fare well with a similar amount of encumbering regulations and classifications. Still, consumers lose in either labeling system. In my opinion, one of the biggest hurdles to the success and expansion of premium New World wines is the opaque nature of their identity or blatant misdirection/concealment of origin with marketing schemes. In 2015, the top three selling wine brands in the U.S. were Barefoot, Sutter Home, and Franzia. Peruse the bottom two shelves of supermarkets and you'll find the other brands like Apothic and Cupcake that land in the top 20. These are all wines without "provenance", or in wine-speak, an identifiable source. They're made from grapes sourced from the cheapest contract vineyards all over California. To keep consistency of taste year after year, these wines are seriously doctored with additives, chemicals, and interventionist techniques like reverse osmosis to reduce alcohol content. In order to compete with the mega-brands like Constellation, Gallo, The Wine Group, and Treasury Wine Estates who own all the aforementioned brands, smaller sub-premium brands focus lots of energy on branding and label design. The main example in the Eater article, Mouton Noir wines, is a serious winemaker producing better-than-plonk wines. Yet his labels focus on catching attention, looking hip, and making puns. I suppose this is the strategy you have to take to stand out and capture customers. I suppose it speaks well to your target audience of Millennials. Conventional advertising theory would assert that this is the winning strategy. Make your brand unique. Stand out. Catch the customer's eye. Sadly, this is an effective strategy for sales but not for informing the customer of anything substantial. The label strategy is just like any other consumable product: buy this lifestyle, buy this emotion, buy this to show off to your friends. These labels don't educate the consumer or guarantee a product's quality. I recently took the above photo of the back label on a bottle of a Vin Gris de Cigare from Bonny Doon. Owner Randall Graham is known for being a trendsetter among the American wine industry, and I hope others follow suit. I love the amount of useful information they put on a label. You can see they list the grape varietals, the winemaking style, the fact that they added tartaric acid and yeast nutrients, used bentonite for fining, and exactly how much sulfur dioxide exists in the bottle. This is a phenomenal amount of info for consumers. If you're a natural wine zealot, you may think 60 ppm of SO2 is too much, or be disappointed that they had to acidulate the wine. But at least those zealots know what is in the bottle and can decide to compromise their principles, or refuse to drink it. I don't universally avoid those winemaking techniques, especially on a wine in this price range (<$20). However, when I'm buying a $30+ bottle of wine, I expect to pay for better quality grapes, which come from greater attention in the vineyard and cellar. I'm really disappointed when I discover a high-end or boutique producer is charging top dollar but acidulating, watering back, or adding powdered tannins to their wines. I want to be paying for grapes of the highest quality, where my dollar directly goes to the attention paid to the vineyard. I don't want to be paying for inferior grapes that are "corrected" into decent wine. All I'm buying at that point is marketing. Put whatever design or artwork you want on the front label. I understand that winemakers or corporations have to grab attention on the shelf or that they want to express their artistic style. Back labels like those on Bonny Doon wines provide a commendable level of transparency. Other wine producers should take notice and follow their lead. For the past few months, professional wine journalists and bloggers have been debating the concepts of the "hipster somm" and "natural" winemaking. The debate boils down to this:

1) Apparently younger somms in NYC have started to favor wines made in what they believe to be Old World style: low in alcohol, high in acid, and made by winemakers who swear to zero intervention; 2) These somms even like wines with hints of Brettanomyces, a verifiable wine flaw caused by undesirable yeast strains that make wine smell like wet barn animals (sulfur); 3) The somms favor adherents of "natural" winemaking, which is typically defined by biodynamic farming, not adding excessive (or any) sulfites as preservatives, using only native vineyard yeasts, and not doctoring wine with tartaric acid, sugar, grape concentrate, etc. to make up for a flawed wine. 4) Wine journalists hit back that the form of "natural" winemaking which "hipster somms" favor equates toward asceticism. The strictest form of non-intervention imposed by the hipsters leads to bad wine. Modern methods and New World styles are not inherently wrong. OK. Clear as mud? What I can gather from this ongoing war of words is a lot of over-exaggeration. The desire for authenticity and integrity in wine is nothing new or hip. People who pay a lot of money for fine wines want a pure expression of the grape varietal(s). But so many wines today are clouded in mystery as to their contents. Along with the organic and non-GMO movements, the natural wine movement is rightly seeking clarity about what's in the bottle. However, some purists take it pretty far. Is it defiling or desecrating the wine to add small amounts of tartaric acid to balance out flabbiness? Is using a controlled, cultured yeast instead of native vineyard yeast an abomination? No. The problem is that, unless a vintner details their winemaking process on their website or on the bottle's label, you have no clue how that wine is made. A $5 wine you find on a liquor store shelf is most certainly doctored with sugar, acid, and other additives to make up for cheap quality. But the $15, $20, or even $50 bottle you buy for a special dinner may be just as doctored up, too. The hipster somms may be fanatics, but they're driving the industry to improve their transparency, and through that - each producer's winemaking skills. Wine journalist Monty Waldin does a stellar job in clarifying the debate from a knowledgeable insider's perspective: https://grapecollective.com/articles/monty-waldin-on-hipster-somms-and-why-black-magic-wine-is-delicious-wine Megan Krigbaum published a great article today in Punch about bargain-buster wines and their provenance. Much of the impetus for creating Vineration is the belief that good wine can come in a variety of price ranges, but that wine must be honestly made.

Many of the industrial wine producers, such as The Wine Group who Megan researches in this article, are so shady about what they put into a bottle. There is no way for the average consumer, much less a journalist, to discover how what their wines are made. But I can guarantee it isn't simply fermented grape juice. It's not that unfined wines are inherently better, or that adding sulfites is wrong... It isn't. The problem with inexpensive wine is that there is no transparency in how it's made. Consumers should know that their cheap wine is more of a chemistry experiment than it is real wine. The best comparison I can think of is between fruit juices. On the juice isle of the supermarket, it's clearly marked which products are 100% real fresh-squeezed juice, with no preservatives or additives, and which is the sugary quasi-juice, with 10% juice concentrates, loads of hi-fructose corn syrup, ascorbic acid, artificial colors, and loads of other ingredients. People still buy Capri Sun, Hi-C, and other fake juice, but at least they can read the ingredients on the back of the label. They know what they're getting. We wine drinkers don't. Last month, my hometown newspaper, the Tampa Bay Times, published a two-part investigative series into the farm-to-fable concept in restaurants and farmers markets. This groundbreaking story unearths the truth that - surprise, surprise - most restaurants and retailers that tout themselves as "farm-to-table" are liberally stretching that term, if not boldly lying about it. Here are links to the articles:

Part 1: Farm-to-Table Restaurants Part 2: Farmers Markets While this investigation only covered one region of Florida, it's not an unreasonable assumption to believe this goes on all over the country. It's too difficult for consumers to verify the source of produce, seafood, and meat, so we're forced to take vendors at their word. Journalism like this puts the pressure on retailers to be honest and the government to put more regulation and enforcement in place. Similarly, half-truths and outright lies exist in the wine industry. It's impossible to verify most claims found on a bottle's label in the store unless you already know the producer or have time to kill in the aisle Googling for information. If you live near a wine region, you have the luxury of being able to visit the winery and ask direct questions. But even then, some claims can be stretched or generalized by tasting room staff. I'll keep on the lookout for good investigative journalism on these practices by winemakers. We all deserve to be eating and drinking authentic products. Take some time and listen to the "I'll Drink To That" podcast episode featuring Jeffrey Patterson, winemaker and owner of Mount Eden Vineyards. I love his approach to winemaking.

Today I drummed up this quote from him, and it struck me as incredibly true in light of the dinner we spent with friends last night. We drank a reserva Malbec which I had carried around Argentina for weeks looking for a place to ship a case home. Upon uncorking the 2011 Jose Luis Mounier Reserva Malbec, it was too bold and too tannic. Disappointing after telling a great story about the beautiful estate and the bottle's journey. But I loved how the wine opened up over the course of the next hours, and how as the tannins settled in my mouth, the flavors began to come through. “Martin’s only mentor was this old-world Frenchman, Paul Masson. Wine in his world was not as it is today. Wine was fundamental, sometimes great, sometimes not-so-great. Paul Masson once said, ‘I don’t care how a wine tastes, I care about how a wine drinks.’ The meaning is that the last glass is the best glass – that wine should evolve over the course of an evening. This is meaningful because wine criticism today is only a brief sniff-sip-spit regimen. One cannot truly appreciate a wine’s true qualities and future potential without spending an evening with it. “ Jeffrey Patterson, Winemaker, Mount Eden Vineyards In my research about the much-loathed Three Tier System of the American alcohol industry, I came across this interesting article. Featured in Washington Monthly in 2012, it explores the agglomeration of the alcohol industry and the vertical integration of the production-distribution-retail model as large corporations break down barriers. The article mostly examines the beer industry, but similar trends can be found in the wine industry. I loved this quote:

"Horizontal integration of alcohol production. Vertical integration of distribution and retail. Loosened local regulations. National chain stores. Streamlined marketing. Volume pricing. Alcohol as an ordinary commodity. America resembles Britain more and more each passing day. How do you like them apples?" The article also examines the phenomenon from a perspective of curbing alcoholism, in relation to high levels of alcoholism in Britain. While I readily admit that alcoholism and binge drinking are growing problems, I'm less sure that the Three Tier System does much to prevent it. I have a hard time believing raising alcohol prices prevents alcoholics from getting drunk. And binge drinking is a social issue tied to not being raised with a healthy respect for alcohol, the age 21 drinking law, and Millennial "late blooming". Overall, the Three Tier System helps corporate wine producers and can hurt independent, small-scale winemakers. The incentives are stacked in favor of large wineries who can move lots of standardized product. And those corporations only continue to grow and acquire more labels. |

Blog

Other non-travel ramblings on wine and business. Archives

December 2018

Categories

All

|

|

All content is original property of Vineration unless otherwise noted.

Not permitted for reproduction. © COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed